Religious centre of Champa - My Son Sanctuary 949; The art of Bài Chòi in Central Viet Nam 01222; Art of pottery-making of Chăm people 01574

What and Why

The red masonry ruins of Mỹ Sơn was the religious centre of Champa (Cham: ꨌꩌꨛꨩ, Campa). The triumvirate of Mỹ Sơn (religious), Trà Kiệu (political) and Hội An (commercial) formed a straight axis of the powerful Champa as early as the 2nd century CE, until it was annexed by Vietnam in 1832 CE.

Hinduism, adopted through conflicts and conquest of territory from neighbouring Funan (Vietnamese: Phù Nam) in the 4th century CE, shaped the art and culture of the Champa kingdom for centuries and put Mỹ Sơn on the map. Temples are dedicated to the worship of the god Shiva (Sanskrit: शिव, Śiva), in various iconic forms since the period. The site is the earliest Hindu temples in the region as is often compared with other more famous counterparts in Southeast Asia, such as Borobudur of Indonesia, Angkor Wat (Khmer: អង្គរវត្ត) of Cambodia, Bagan (Burmese: ပုဂံ) of Myanmar and Ayutthaya (Thai: อยุธยา) of Thailand, all these being UNESCO WHS. The site is also the longest uninterrupted period of development of any monuments in Southeast Asia. Their technological sophistication of the temples is evidence of Cham (Cham: ꨌꩌ, Čaṃ) engineering skills while the elaborate iconography and symbolism of the tower-temples give insight into the content and evolution of Cham religious and political thought.

The site was only rediscovered in 1898 CE by French archaeologists after being left to rot in the 18th to 19th century CE. Unfortunately much of the site has been destroyed by the American bombing during the Vietnam War. The entire ruin is now swamped in the jungle, ironically Mỹ Sơn means beautiful hill in Vietnamese.

Toponymy

Mỹ Sơn means a beautiful hill in Vietnamese and Chinese (Chinese: 美山, meishan).

See

Mỹ Sơn consists of more than 70 monuments over a fairly large area. When the French began exploring Mỹ Sơn in the late 19th century CE, one of the main artists-cum-archaeologists Henri Parmentier found the remnants of 71 temples. He classified them into 14 groups, including 10 principal groups each consisting of multiple temples. For purposes of identification, he assigned a letter to each of these principal groups: A, A', B, C, D, E, F, G, H, K, mainly according to location and damage extent of the ruin.

There are generally four types of buildings, based on Hindu architecture:

Group H

The first group of monuments from the entrance. Group H represents the Bình Định style of architecture and also the latest.

Group B, C and D

This is the most heavily represented style at Mỹ Sơn, and is known for its intactness and beauty. One of the striking features was that many of these architectures show western influence, as in one of the fallen pillars. This pillar shows a Doric base plus a Hindu base, showing the wave of religious influence from the west.

Group B and C's clusters include many other well maintained and un-ruined constructions.

One of the iconic structures is what is referred to the lingam (Sanskrit: लिङ्गम), which is the symbolic representation of Shiva. It usually looks like a western anvil.

According to Encyclopædia Britannica, the lingam is an aniconic object found in the sanctum of Shiva temples that symbolises Shiva and is revered as an emblem of generative power. The top bullet-like structure is Shiva and sits on an anvil based lipped, disked structure that is an emblem of goddess Śakti (Devanagari: शक्ति) called the yoni (Sanskrit: योनि, meaning womb). Together they symbolise the union of the feminine and the masculine principles, and 'the totality of all existence'. The square base is also interpreted as Brahmā (Sanskrit: ब्रह्मा). The tip of the anvil often represents the river flow direction in the region.

Group A

The most well-preserved construction area, the above shows the almost intact fire-house and a semi-collapsed temple.

Many of buildings show typical elaborate Hindu sculptures and carvings.

Group E

The main gateway as in the first picture.

Museum

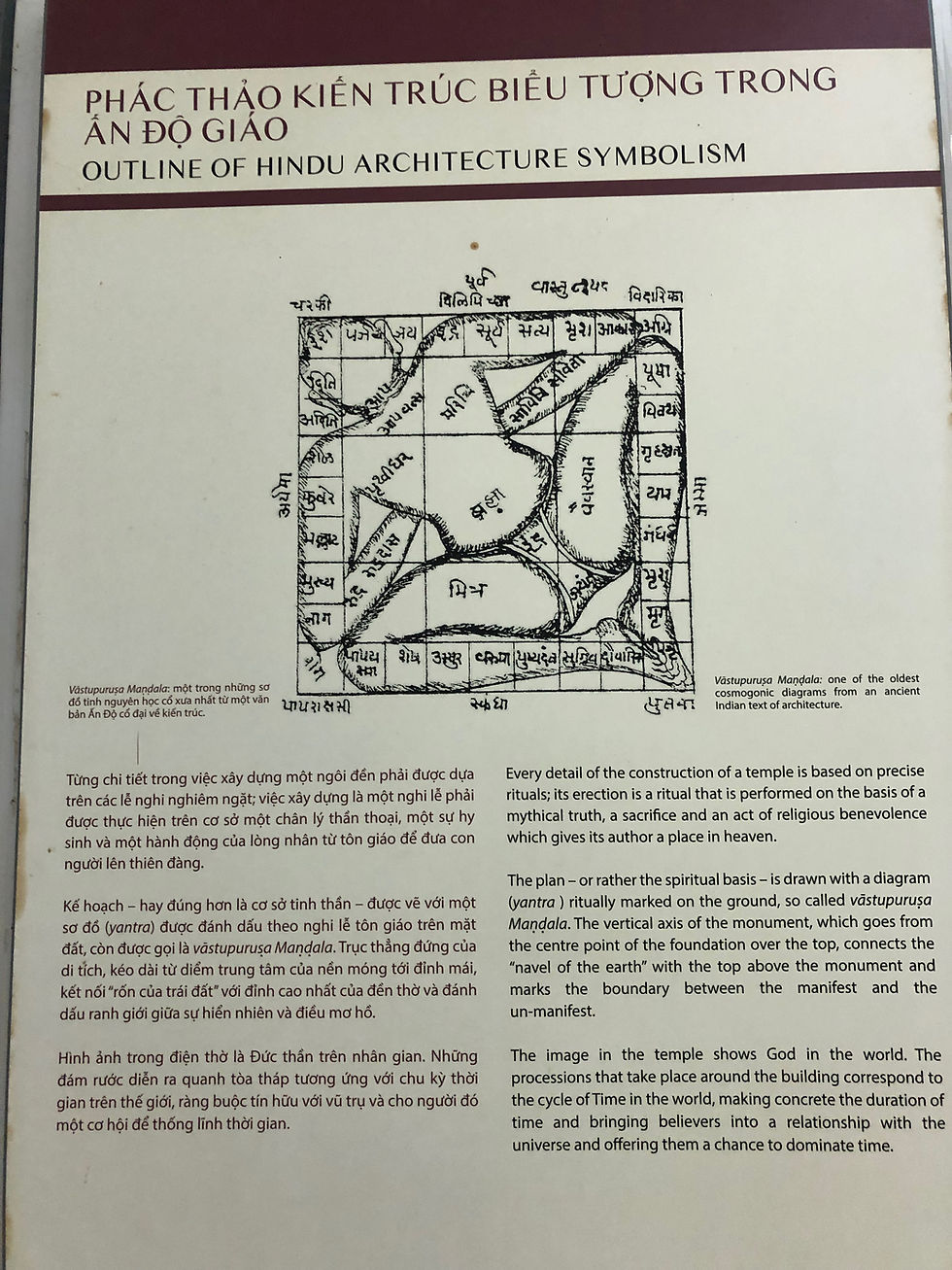

There is a very good museum right at the entrance of the park. One of the most important description shows how the temples are manifested and planned, as above. The navel of the body represents the centre of the system and is the main connexion to heaven.

Buy and Do

Bài Chòi

During the night we attended a cultural show featuring another UNESCO ICH, Bài Chòi. Bài Chòi literally means a game in a house in Vietnamese and is an assortment of cultural arts in including music, poetry, acting, painting, boardgames and literature, for social development within the central Vietnamese village communities. The video below shows a Bài Chòi singing performance.

It also features a bingo-like board game within the community, although it is difficult for visitors like us to appreciate what is going on. This particular community social practices prevail mainly in Central Vietnam.

Cham pottery (Gốm Chăm)

One of the most important souvenirs to buy in Central Vietnam is Cham pottery (Gốm Chăm). Cham pottery has been there for over a millennium since the Champa era, but now this artisan work is restricted only the very small Cham community is Central Vietnam. According to the artisans, their sculptures and potteries are not only daily utensils, but more importantly, they are an intermedia for them to connect with their deities.

Cham pottery is distinctive from any other type in the world because it is 100% handmade at all stages. While other pottery is made from a rotating wheel, Cham potters use their feet to move around the clay mixture while using their hands to shape the pottery with no machineries and moulds. The potteries are not hardened inside a kiln but put on a fire which only uses wood and straw, and takes from five to eight hours depending on the size of the product. According to Cham tradition, a potter must choose a good date for firing the pottery and before starting the firing process, and the potter must conduct an offering ritual dedicated to the deities, praying for their support for making the potteries beautiful.

Cham potteries range from simple home utensils to objects of worship, statues, reliefs and decorative patterns, with most patterns reflective of faith natural sceneries. We visited the Da Nang Museum of Cham Sculpture (Bảo Tàng Nghệ Thuật Điêu Khắc Chăm Đà Nẵng) in Da Nang (Đà Nẵng) to see the Cham potteries and its cultural heritage. Cham pottery is now firmly inscribed as an ICH.

Eat and Drink

As mentioned in the earlier blog, Vietnamese food is full of rice-paper wraps. One of our favourites during this journey is the bánh xèo, meaning a sizzling pancake in Vietnamese, which is some kind of a crispy egg-nacho wrapped by rice-paper. We had this wonderful treat in Trà Quế Vegetable Village. During this tour, we also visited a tiny local rice paper shop and made our own rice-sheet.

Getting There and Around

Mỹ Sơn is hidden deep inside a jungle, and while it is only 30 minutes away from Hội An, it is next to impossible to locate. Roads are rugged and terrible and the area is often raining. Join a local tour and spend half-a-day there. The entrance fee to the site is VND 150,000₫.

UNESCO Inscriptions

Between the 4th and 13th centuries a unique culture which owed its spiritual origins to Indian Hinduism developed on the coast of contemporary Viet Nam. This is graphically illustrated by the remains of a series of impressive tower-temples located in a dramatic site that was the religious and political capital of the Champa Kingdom for most of its existence.

The art of Bài Chòi in Central Viet Nam is a diverse art combining music, poetry, acting, painting and literature. It takes two main forms: ‘Bài Chòi games’ and ‘Bài Chòi performance’. Bài Chòi games involve a card game played in bamboo huts during the Lunar New Year. In Bai Choi performances, male and female Hieu artists perform on a rattan mat, either moving from place to place or in private occasions for families. The bearers and practitioners of the art of Bài Chòi are Hieu artists, solo Bài Chòi performers, card-making folk artists and hut-making folk artists. The art of Bài Chòi is an important form of culture and recreation within village communities. Performers and their families play a major role in safeguarding the practice by teaching song repertoires, singing skills, performance techniques and card-making methods to younger generations. Together with communities, these performers have set up nearly 90 Bài Chòi teams, groups and clubs to practise and transmit the art form, which attracts wide community participation. Most performers of the art learn their skills within the family and the skills are mainly transmitted orally, but artists specializing in Bài Chòi also transmit knowledge and skills in clubs, schools and associations.

Chăm pottery products are mainly household utensils, religious objects and fine art works, including jars, pots, trays and vases. They are made by women and viewed as an expression of individual creativity based on the knowledge transmitted within the community. Instead of using a turntable, the women revolve around the piece to shape it. The pottery is not glazed but fired outdoors with firewood and straw for seven to eight hours, at a temperature of about 800 degrees Celsius. Raw materials (clay, sand, water, firewood and straw) are collected locally, and the knowledge and skills are passed on to younger generations within families through hands-on practice. The practice gives women the opportunity to exchange and interact with each other in productive labour and social activities as well as in vocational education for their children, further enhancing their role in society. It can also help bolster family income and safeguard the habits, customs and cultural identities of Chăm people in Viet Nam. However, despite many safeguarding efforts, the viability of the craft is still at risk for several reasons, including the impact of urbanization on access to raw materials, insufficient adaptation to the market economy and lack of interest among younger generations.

References

Comentários